Fall is almost here, a busy show season has emerged, and foals on our small farm are growing up quick. As the tenth year of this new century is soon beginning, our thoughts and conversations with other friends in the Percheron horse world have been turning toward the age-old questions of what stud to breed to, what the judges are looking for, and what to strive for in the 2010 foal crop. As we talk to other breeders, draft farriers, teamsters, dressage fanciers and riders, our conversations often seem to circle back around to the same issues of judging, judge education, and breed standards.

Fall is almost here, a busy show season has emerged, and foals on our small farm are growing up quick. As the tenth year of this new century is soon beginning, our thoughts and conversations with other friends in the Percheron horse world have been turning toward the age-old questions of what stud to breed to, what the judges are looking for, and what to strive for in the 2010 foal crop. As we talk to other breeders, draft farriers, teamsters, dressage fanciers and riders, our conversations often seem to circle back around to the same issues of judging, judge education, and breed standards. One thing that we treasure about the draft horse world is that it is steeped in a rich tradition of big horses, antique equipment, an honorable history, and multi-generational spirit. These traditions, while perhaps a bit romantic, are clearly worth preserving. Those of us who admire and own draft horses are often mindful of a different era, an era where life was both simpler and harder. A more straightforward world where what mattered was the ability of a farmer, logger, or teamster to use his stock, tools, knowledge and abilities to get a job done. A place where there were fewer rules and regulations.

One thing that we treasure about the draft horse world is that it is steeped in a rich tradition of big horses, antique equipment, an honorable history, and multi-generational spirit. These traditions, while perhaps a bit romantic, are clearly worth preserving. Those of us who admire and own draft horses are often mindful of a different era, an era where life was both simpler and harder. A more straightforward world where what mattered was the ability of a farmer, logger, or teamster to use his stock, tools, knowledge and abilities to get a job done. A place where there were fewer rules and regulations.That said, the world has changed, and the Percheron world is changing with it. Within the draft horse industry, big money often drives the big hitches, professional managers handle barns of horses, many big hitches are really more about advertising than about getting work done, auction prices are at record highs with good animals fetching tens of thousands of dollars, the registered Percheron PMU market is still importing horses into the USA, the riding and cross-breed market is expanding and also exerting new influences upon the breed. With these new demands has come pressure within breeding programs to meet new market opportunities and forces. Breeders have new tools (such as semen shipment, embryo transfer and artificial insemination) to rapidly meet buyer demands.

Artificial insemination is creating a situation whereby a few stallions are being used to breed hundreds, if not thousands of mares each year. All this money, marketing and new influences are causing rapid evolution of some of the more popular draft horse breeds, and are also rapidly restricting the gene pool available to future generations. The importance of the hitch market, combined with economic pressures and shipped semen may accelerate the loss of genetic diversity. In aggregate, our individual choices are rapidly changing the genetic heritage that we will leave to those breeders who follow.

Artificial insemination is creating a situation whereby a few stallions are being used to breed hundreds, if not thousands of mares each year. All this money, marketing and new influences are causing rapid evolution of some of the more popular draft horse breeds, and are also rapidly restricting the gene pool available to future generations. The importance of the hitch market, combined with economic pressures and shipped semen may accelerate the loss of genetic diversity. In aggregate, our individual choices are rapidly changing the genetic heritage that we will leave to those breeders who follow. In the past, many draft horse breed associations have gotten away with not having a breed standard because it wasn’t really necessary. We believe that this picture is now changing, both for Percherons as well as for many other draft horse breeds. New technologies, such as artificial insemination, embryo transfer, computer management, better transport and even cloning are allowing a few animals to dominate a breed’s gene pool. This wasn’t even a possibility less than three decades ago. The potential for extremely fast evolution of a breed is not just a theoretical possibility; it is already today’s reality.

In the past, many draft horse breed associations have gotten away with not having a breed standard because it wasn’t really necessary. We believe that this picture is now changing, both for Percherons as well as for many other draft horse breeds. New technologies, such as artificial insemination, embryo transfer, computer management, better transport and even cloning are allowing a few animals to dominate a breed’s gene pool. This wasn’t even a possibility less than three decades ago. The potential for extremely fast evolution of a breed is not just a theoretical possibility; it is already today’s reality. A stud owner’s ability to promote their stallion(s) is now based upon rated or National in-hand shows, the All American program, performance venues and marketing. Financial rewards flow to those who campaign and win at the “big” shows, and to the victors go the genetic spoils- the capacity of a stud to pass his genes on to larger and larger fractions of the quality brood mares, and the ability of a winning stud farm to capture lucrative contracts for shipped semen. But what are the criteria that judges use for breed specific halter classes or for the All American program? What do we want our horses to become over the next two decades or the next century? The old saying “If a little is good, more is better” seems to determine what people often look for in a Percheron, as judges, buyers and breeders appear to demand new, better and different. Many judges are rejecting established breed phenotypes as being old fashioned, not “hitchy,” or not tall enough. But others believe that Percherons have historically been a diverse breed from its very origins at Haras du Pin. Many believe that the Percherons are split into two (or more) types: halter and hitch (with “drafty” horses capable of a day’s work pulling a distant third). But a breed standard would work to codify breed characteristics, an important element to any breeding program and to the breed itself.

A stud owner’s ability to promote their stallion(s) is now based upon rated or National in-hand shows, the All American program, performance venues and marketing. Financial rewards flow to those who campaign and win at the “big” shows, and to the victors go the genetic spoils- the capacity of a stud to pass his genes on to larger and larger fractions of the quality brood mares, and the ability of a winning stud farm to capture lucrative contracts for shipped semen. But what are the criteria that judges use for breed specific halter classes or for the All American program? What do we want our horses to become over the next two decades or the next century? The old saying “If a little is good, more is better” seems to determine what people often look for in a Percheron, as judges, buyers and breeders appear to demand new, better and different. Many judges are rejecting established breed phenotypes as being old fashioned, not “hitchy,” or not tall enough. But others believe that Percherons have historically been a diverse breed from its very origins at Haras du Pin. Many believe that the Percherons are split into two (or more) types: halter and hitch (with “drafty” horses capable of a day’s work pulling a distant third). But a breed standard would work to codify breed characteristics, an important element to any breeding program and to the breed itself. It also follows that people have to ask themselves, “Just what are those judges really looking for?” That is an important question because as some traits seem to be changing rapidly, others are not. Should judging criteria be based on new, improved horses or horses that represent what was the standard in the past, or some mix in-between? Without a standard, it is up to any one person’s opinion as to what to judge on, and it is hard to find ways to educate potential judges, breeders and owners as to what the ideal Percheron should look like. A breed standard would allow for judge education, something that is now mostly lacking within the Percheron Horse Association of America. Judge education is important because rated Percheron shows often determine those animals that will be the genetic stock for future generations.

It also follows that people have to ask themselves, “Just what are those judges really looking for?” That is an important question because as some traits seem to be changing rapidly, others are not. Should judging criteria be based on new, improved horses or horses that represent what was the standard in the past, or some mix in-between? Without a standard, it is up to any one person’s opinion as to what to judge on, and it is hard to find ways to educate potential judges, breeders and owners as to what the ideal Percheron should look like. A breed standard would allow for judge education, something that is now mostly lacking within the Percheron Horse Association of America. Judge education is important because rated Percheron shows often determine those animals that will be the genetic stock for future generations. One can’t preserve what hasn’t been defined. This thought is central to understanding why the Percheron Horse Association of America needs a breed standard. Some draft horse breeds have been progressive enough to have a standard already. Shires and Suffolk Punches are two such breeds and most people involved with these breeds are proud to have a breed standard.

One can’t preserve what hasn’t been defined. This thought is central to understanding why the Percheron Horse Association of America needs a breed standard. Some draft horse breeds have been progressive enough to have a standard already. Shires and Suffolk Punches are two such breeds and most people involved with these breeds are proud to have a breed standard.Naysayers will argue that Percherons are too diversified to have a standard. But there are other breed registries that have dealt with this issue in a satisfactory manner. It is not impossible to write a standard for a breed that has gotten to the point where different types or lines have been developed. But it might be necessary to write the standard to define those differences. One only has to look to the Welsh Pony and Cob Society of America (WPCSA) to see an example of how this issue can be effectively handled with finesse and an awareness of the diversity of the breed. The WPCSA has four sections of Welsh ponies within their standard (two types of Welsh Mountain Pony, Sections A and B, and two types of Welsh Cob, Sections C and D). There is a lot of diversity between the four sections and yet, all four sections are considered one breed, with similar characteristics. These differences between the types have been successfully written into one standard. Welsh Ponies are shown with each type having their own halter classes as well as separate performance events. The WPCSA is a great example of how diversity can be worked into a breed standard. It should be considered carefully as a model for a breed standard that encompasses more than one type of horse within a breed.

When the children of our children’s children look out their window into the pasture, we hope that the vision of a herd of glorious Percheron mares meets their gaze. We wish to think that those mares will look like the very same mares that greet my eyes each morning. A breed standard will help make that goal a reality.

By: Jill Glasspool Malone, PhD and Robert W. Malone, MD, MS (written in 2008, edited 2010 -copyright 2008)

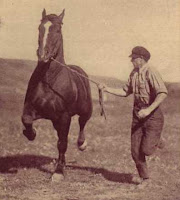

*All photos were taken in the 1800s or very early 1900s. Note that most of the Percherons on this page were from France, where there were strict breeding standards: with studs chosen from stables of Haras du Pin.

No comments:

Post a Comment